The Eratosthenes experiment

How can you measure the Earth with your mom's tape measure, and at the same time, prove that it's not flat? The solution to this silly question is simple: Eratosthenes' experiment. Eratosthenes is famous for having calculated with great precision the size of the Earth in the 3rd century BC, simply by measuring the shadow of his stick, a couple of data, and with a very elegant mathematical deduction.

Taking advantage of a trip I was going to make to London, I wanted to carry out the same experiment, and with my mother's tape measure and the antenna of an old radio (something thin and long that could pass through airport controls), I set out to measure the Earth.

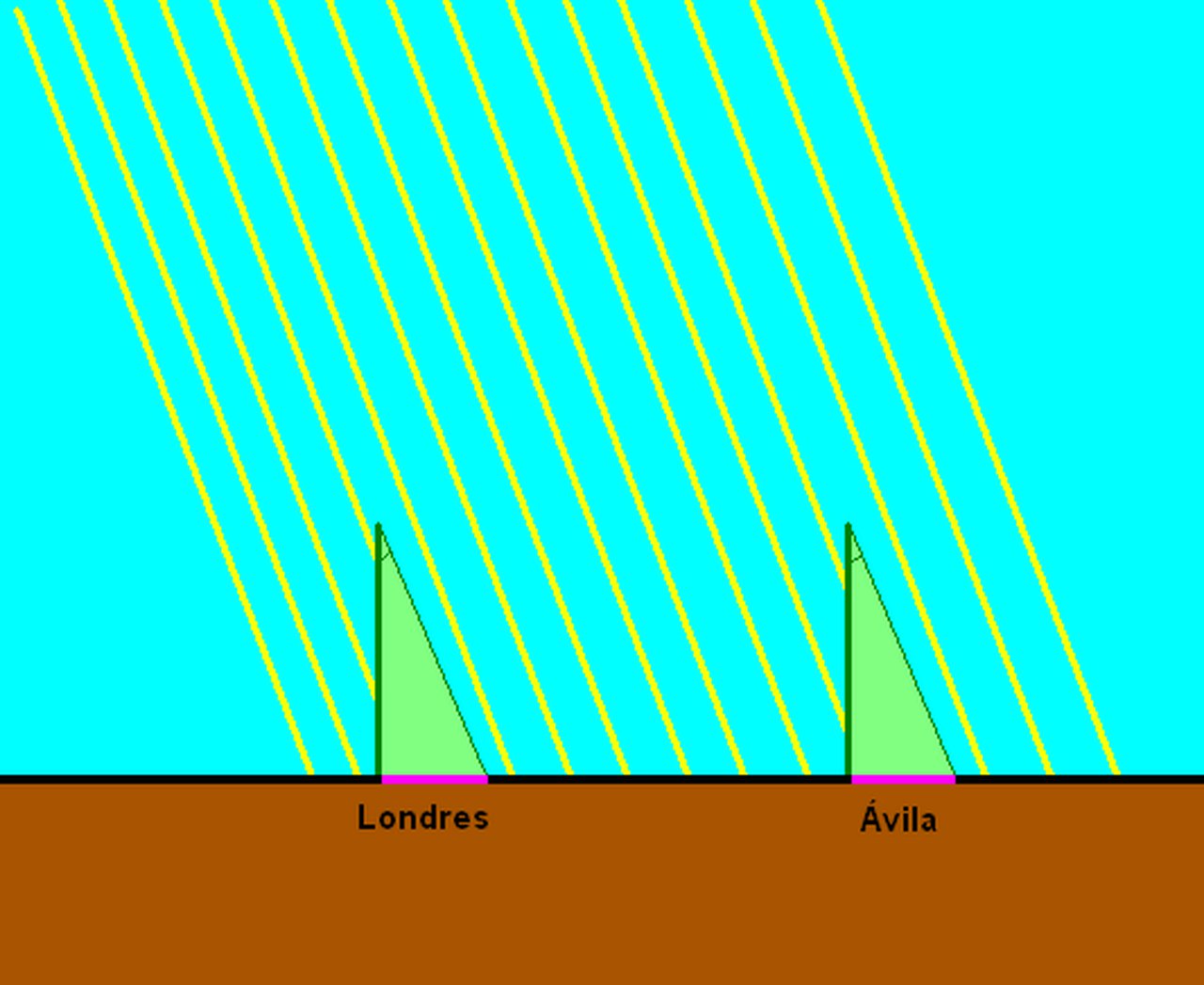

The principle is very simple. The sun is very, very far from the Earth (147 million kilometers) so its rays reach us parallel. Therefore, if the Earth were flat, at the same time in London and Ávila, the shadow cast by a stick of the same size (green) on the ground would be the same (purple):

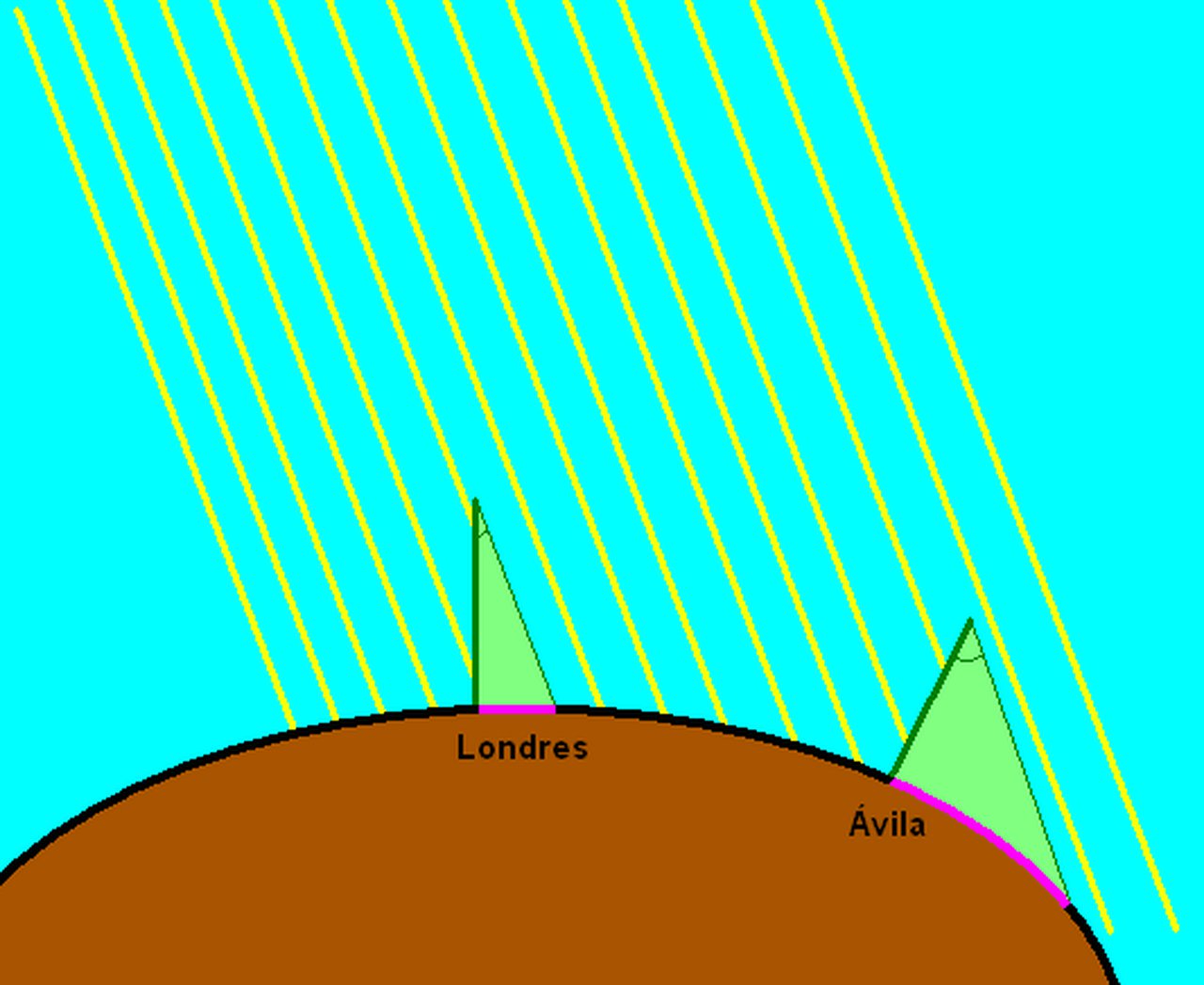

But if the Earth were round, the shadows cast by the two sticks of the same size in London and Ávila would be of different sizes.

Then, by measuring the length of the shadow of the antenna at the same time in Ávila and London and verifying that the lengths are different, it is shown that the Earth is round.

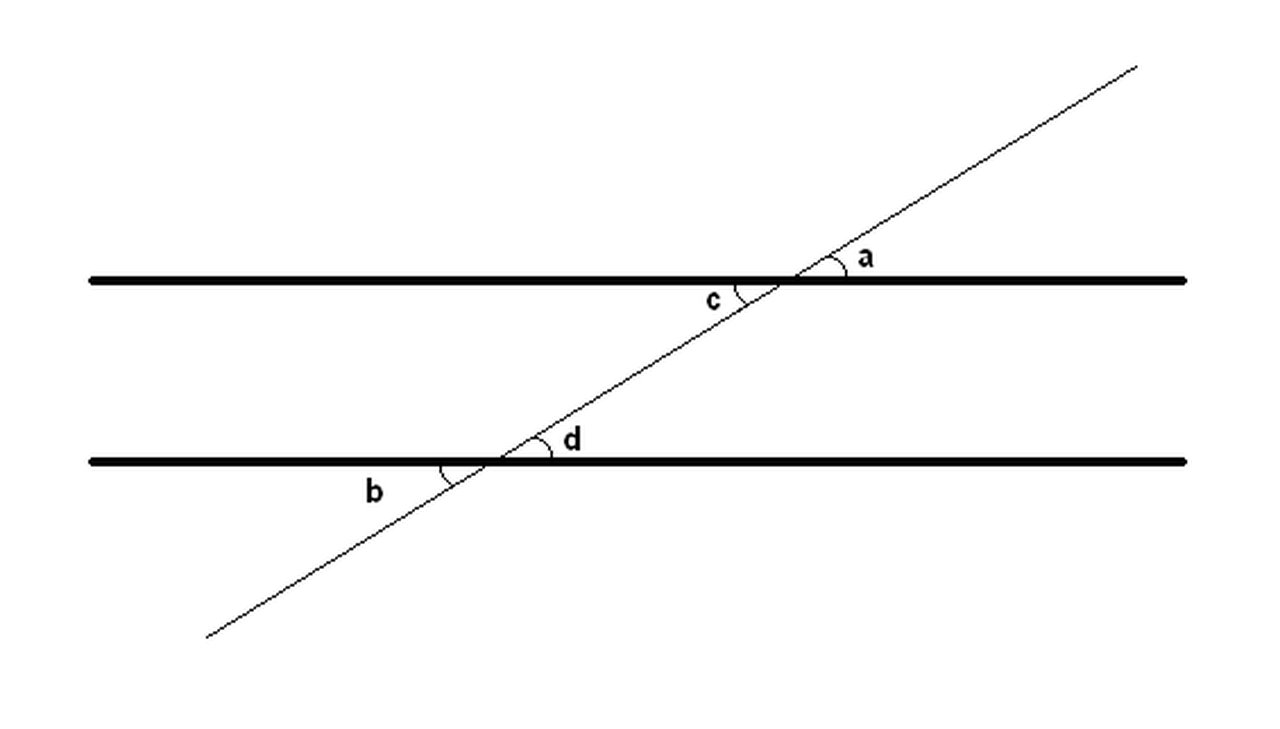

But that's not all. Knowing the difference in the lengths of the shadows, we can also know the size of the Earth: this is discovered through a simple mathematical reason: If two parallel lines are cut by a third line, the alternate interior angles are equal:

That is, angles a, b, c, and d are equal.

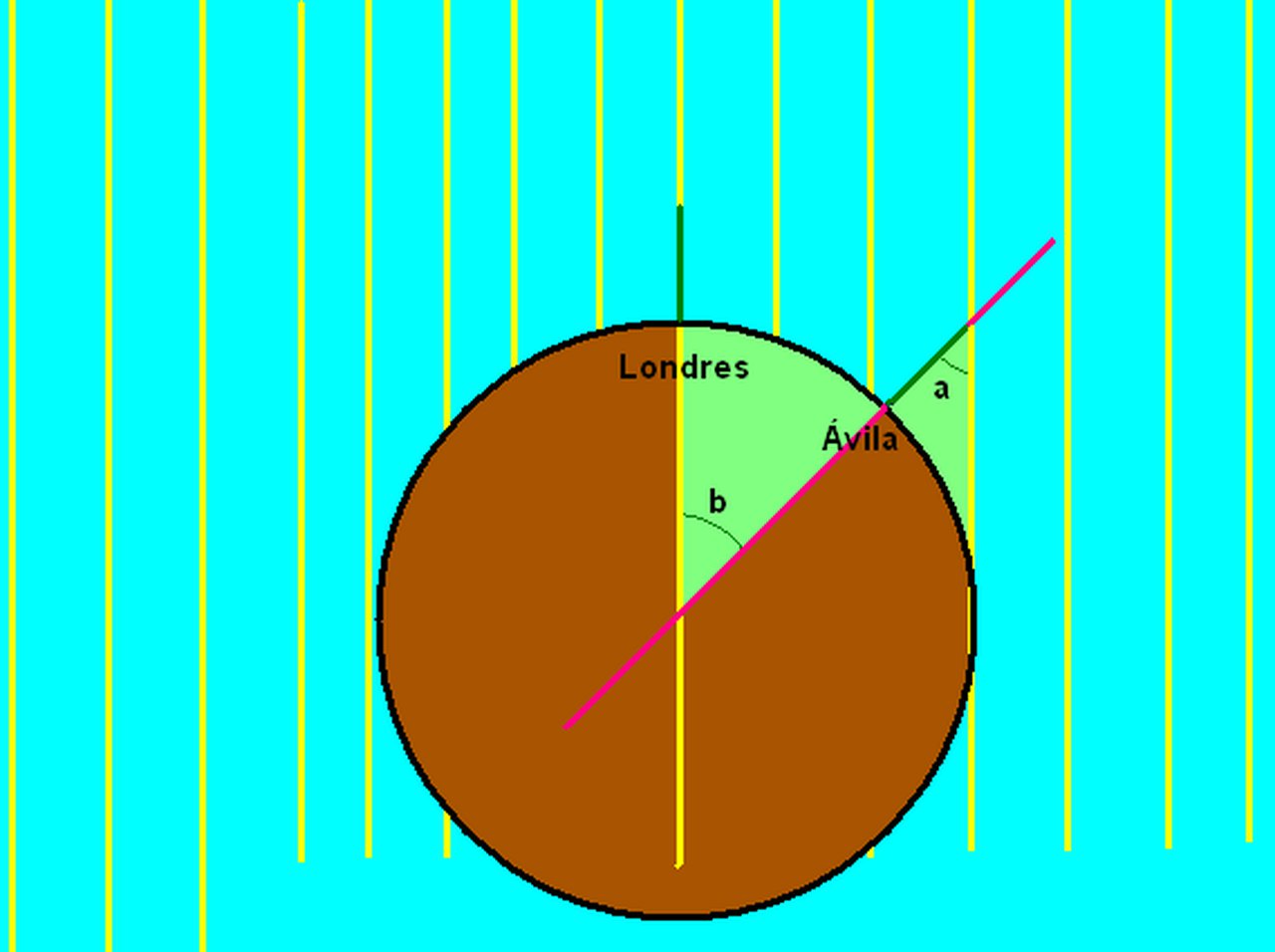

We already have the parallel lines, they are the rays of the sun, and the third line, which crosses the parallel lines, is the imaginary line that arises from the extension of the stick I use to measure to the center of the Earth:

As we have seen, angles a and b are equal, therefore, once we know angle a and knowing the distance between Ávila and London, we can quickly calculate the radius of the Earth.

This is the theoretical approach to the measurement, but putting it into practice is not easy and I have had several problems, which I have solved in a more or less elegant way.

The first one is simple, in the diagram above I assume that the sun shines on London perpendicularly, and that doesn't happen. To solve this, I assume that angle a is the difference between the angles of London and Ávila.

The second problem is that the measurements in Ávila and London must be at the same time or on the same day of the year, and I didn't have anyone to measure in Ávila at the same time as I measured in London and I couldn't wait a year for the Earth to be in the same position, so I took the measurements the day before I left and the first day in London and the last day in London and the day after I returned, so that this error would be minimal.

And the third problem is that London is not on the same meridian as Ávila (at the same longitude), so I looked on a map

for the difference in longitudes and calculated the time it takes for the sun to be in the same position for Ávila as for

London, knowing that the sun takes 24 hours to travel 360º:

Longitude London: 0° 4' 56'' O

Longitude Ávila: 4° 40' 21'' O

Diference: 4° 35' 25''

Time that the sun takes to travel 4° 35' 25'':

$$ 4^\circ 35' 25'' \times \frac{24 \text{ h}}{360^\circ} = 18 \text{ min} $$

So I measured the length of the shadow 18 minutes later than the time I measured in London.

I made all these measurements (the first one is obvious that I wrote down the length of the shadow wrong, most of them are useless, I made them at different times to have more possibilities to measure it in both places and the ones in bold are the ones I used).

Ávila 11 - 4 - 2007

18:44 Antenna: 48 cm Shadow:

135 cm Angle: 70° 25' 36,75''

London 12 - 4 - 2007

15:39 Antenna: 48 cm Shadow:

52 cm Angle: 47° 17' 26,2''

18:44 Antenna: 48 cm Shadow: 135

cm Angle: 70° 25' 36,75''

Greenwich (0°) 15 - 4 - 2007

18:36 Antenna: 48 cm Shadow:

131 cm Angle: 69° 52'35,58''

18:44 Antenna: 48 cm Shadow:

133 cm Angle: 70° 9' 19,34''

Londres 16 - 4 - 2007

14:20 Antenna: 48 cm Shadow: 44

cm Angle: 42° 30' 37,61''

Ávila 17 - 4 - 2007 (I forgot the antenna..)

14:20 Post: 74 cm Shadow:

41 cm Angle: 28° 59' 19,76''

14:24 Post: 130 cm Shadow:

75 cm Angle: 29° 58' 53,9''

14:30 Post: 275 cm Shadow:

164 cm Angle: 30° 48' 37,13''

14:38 Post: 275 cm Shadow: 168 cm

Angle: 31° 25' 16,09''

Here you can see the antenna providing shade next to Buckingham Palace:

And here the antenna next to the gate of San Vicente of the walls of Ávila.

The London squirrels were very attentive to the experiment:

The math is not complicated:

I obtain the angle by basic trigonometry: the tangent of the angle

$$ \tan a = \frac{\text{length of the post}}{\text{length of the shadow}}$$

The difference of angles gives us what in the diagram I had called the angle a:

$$ a = 42^\circ 30' 37.61'' - 31^\circ 25' 16.09'' = 11^\circ 5' 21.52'' $$

Knowing the distance between London and the point that is at the same latitude as Avila but at the same longitude as London (1210 km) and the difference between the shadow angles in the two cities, I can calculate the radius of the earth, since if the length of a circle is:

$$ l = 2 \pi r $$

which correspond to the 360º of the circumference, therefore, our 11º and pico will give an arc of length proportional to the angle. From this equation we can clear the radius, which is the data we want to know:

$$ l_\text{arc} = a \times \frac{2 \pi}{360^\circ} r \Rightarrow r = \frac{l_\text{arc} \times 360^\circ}{a \times 2 \pi} $$

where l is the length of the arc, a is our angle and r is the radius of the Earth.

Then the radius of the Earth is:

$$ r = \frac{1210 \text{ km } \times 360^\circ}{11^\circ 5' 21.52'' \times 2 \pi} =6251.77 \text{ km} $$

6,251.77 km! The actual mean radius of the Earth is 6,378.14 km, so I've only made an error of

$$ 100\% - \frac{6251.77 \text{ km}}{6378.14 \text{ km}} \times 100 = 1.98 \% $$

only 1.98%. It's incredible that with the materials I've used, such a good result is obtained. Without a doubt, this is one of the simplest, most effective and simple scientific experiments.

I dedicate this entry to everyone who has put up with me when I was rambling on about the experiment, and especially to Clara and María Eugenia, who put up with me throughout the trip to London.

|

Next post: 211 Years Ago Today... |

Previous post: Mar Bean's Holiday |